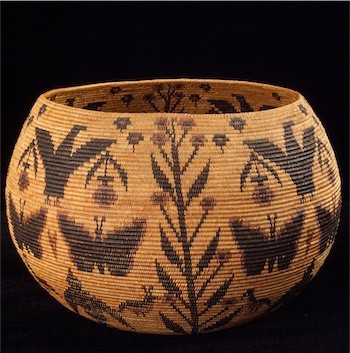

Basket Making is Man’s most ancient craft

Basket Making Worldwide

Basket making survives in many parts of the world today in forms, techniques, and materials similar to those used in past ages. While continuing as a living tradition, it has undergone a revival of interest among crafts people, leading to new forms of expression. Just as weavers make pictures with tapestry, basket makers now use basketry techniques to create sculptures.

Archeologists tell us that the oldest known baskets presently appear to be some unearthed in Faiyum, South of Cairo in upper Egypt; radiocarbon dating tests have shown them to be between 10,000 and12,000 years old. Other Middle Eastern sites, notably in Mesopotamia and Palestine, have produced baskets up to 7,000 years old. A cave in Utah yielded baskets 9,000 years old. The earliest dates are older than any yet established by archeologists for pottery.

Basket making is the weaving of un-spun vegetable fibers, usually to form a container, although basketry techniques have been and still are used to make clothing, hats, shoes, boats, furniture, traps for fish and game, cooking utensils, and houses.

Varieties of Basket Making

There are five types of basket making the one that predominates in an area depends largely upon the native materials available in that area. Coiled basketry tends to use grasses and rushes.

Plaiting flourishes where materials are wide and ribbon-like—the palms of the tropics or the yucca of the deserts. Twining occurs where roots and tree bark are the most readily available materials. Wicker and splint baskets are made where reed, cane, willow, oak, and ash grow.

Traditionally, basket makers gather and prepare their own materials. Until you have grasped the medium, you may prefer to purchase materials from your local craft shop or online, but eventually you may decide to gather your own.

Tools For Basket Making

The main tools of basket making are your own fingers. Beyond that, the implements are few and simple, most of them already in your tool kit or sewing basket.

They include an awl—6 inches is a good size—a utility knife, a jack-knife, 5-inch side-cutting pliers, 5-inch needle-nose pliers, a cloth or plastic measuring tape, a No. 4 or No. 5.

Plus a metal knitting needle, heavy scissors, a crochet hook, a short needle with a big eye such as a tapestry needle, and clip clothespins.

Not all of these tools are required for every basket.

You will also need a large pan for soaking materials; some materials are so bulky that you may prefer to use the bathtub or kitchen sink.

A basket maker does not always know ahead of time how a basket will turn out, since its final shape and size may be governed by the pliability of the materials.

The base is the experimental stage and is usually worked until the basket maker gets the feel of the materials.

By the time the sides are turned up—the point at which problems tend to arise—the materials should be under control.

Whether you make or collect baskets, take care of them by wetting them briefly once a year to restore moisture to the fibers. Dry them quickly in the shade.

If a basket is dirty, wash it gently with a very soft brush dipped in mild soapsuds. Old baskets may need a restorative coat made of 1 part boiled linseed oil to 3 parts pure turpentine.

Use the same solution if you want to darken new baskets slightly. You can dye basket materials with vegetable dyes

Coiled Baskets

A coiled basket is a tour de force: from such insubstantial materials as corn husks, grass, pine needles, raffia, or yarn emerges a basket of considerable solidity. Or such unyielding materials as reeds, vines, roots, or cane are bent and stitched into a tight spiral. Because the radius of the spiral increases continuously, a coiled basket is dynamic, constantly swirling outward.

Coiling is basically a process of wrapping a binder around a core and stitching rows of core together. The core may be a single rod, such as reed or thick rope; it may be two or three rods or a bundle of grass, pine needles, or corn husks. The binder may be raffia, cane, or some other supple material. The core may be exposed by spacing the stitches widely; more often it is covered by the binder.

A soft binder, such as raffia or yarn, is wrapped and stitched using a heavy needle with a large eye. For stiff binder a hole is made through the core with an awl, and the binder is pushed through.

The most difficult part of a coiled basket is the start. The wrapped start is used when the core material can be bent into a tight circle. The knot start is used with very soft core materials or, conversely, when the core is too stiff to bend into a circle. In the latter case the start is made with the binder material; the core is added later.

Mark the starting point of the first row of stitching with a piece of colored thread or raffia. Always begin a change in stitch or pattern opposite that point.

The row currently being incorporated into the basket is called the working row; the row before, into which it is stitched, is the previous row. Turning the basket walls upward from the base is accomplished by placing the working row slightly higher than the previous row. The turn may be either abrupt or gradual.

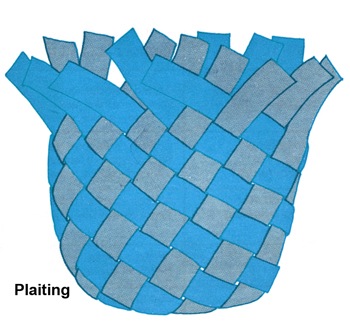

Plaiting: the Fastest Baskets

Plaiting is used all over the world to make everything from sandals to houses as well as baskets. Because materials are likely to be wide, plaiting is usually a fast way of making a basket. However preparation of the materials is frequently long and arduous.

In Mexico many people are born, sleep, and die on a petate, a mat plaited from yucca or palm leaves. In warm climates the natural materials suitable for plaiting are readily available. These include pandanus and coconut leaves, split bamboo, and cane.

But many natural plaiting materials are unavailable commercially, and their distribution in nature is limited. Consequently modern-day plaiters have turned to manufactured and “found” materials, such as cloth, plastic, leather, wallpaper, and even discarded film and magnetic tape.

Plaiting’s basic technique is the over one, under one of plain weave. The two elements may be thought of as the warp and weft of woven fabrics; they are usually of equal size and strength. The typical natural materials are flat and thin, and the resulting basket is light and flexible.

Two-element plaiting is either parallel, as in the bottom of ribbon baskets, or diagonal, as in its sides. In both cases the elements are at right angles to each other; the difference lies in how they are worked. In parallel plaiting one element at a time is added and woven, whereas in diagonal plaiting all elements are in motion simultaneously and could be woven all at once—if the weaver had enough hands. More difficult but more varied in design possibilities is hexagonal plaiting.

Before plaiting with the actual materials, it is a good idea to practice by making a mock-up of strips of paper. In designing your own basket, a mock-up lets you work out the length and number of elements in advance. Where color is desired, mark the paper strips. Then take the mock-up apart; the marked strips indicate the number of colored strips needed. You can now cut materials for the basket to the exact size and number with no waste.

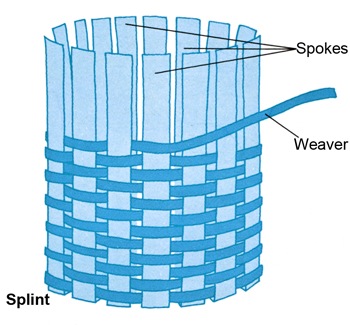

Working with Splint

Splint baskets are the workhorses of basket making. They are the baskets in which farmers transport produce to market. They are laundry baskets. They are the pack baskets favored by guides.

The Passamaquoddy Indians of Maine, the Mohawks of New York, and the Cherokees of the Great Smoky Mountains are famed for their splint baskets. The Shakers made splint baskets of delicate refinement.

The materials of splint basket making are flat, thin strips of wood, usually ash or oak. Spokes and weavers may be the same material, or the weavers may be finer strands of another material.

The weaves are uncomplicated: plain weave—over one, under one—or twill weave—over two, under two. If the basket has an even number of spokes, a new weaver is usually used for each round. With an uneven number of spokes, one weaver is worked in continuous rounds.

Splints from black and white ash trees are traditionally made by pounding a log that has soaked over the winter to loosen the annual rings of growth. Today splints of white ash and oak are cut by machine and are available from firms that sell materials for chair-seat weaving.

All splints must be thoroughly soaked-at least 20 minutes—before working with them. Machine-cut splints have a right and a wrong side; to find the right side, bend the soaked splint. Small splinters will be raised on the wrong side.

The smooth side should be on the outside of the basket; work the base with the rough side facing up. Designing your own splint basket is easy. Since the weavers hold the spokes slightly apart, allow about 1/4 inch between spokes. To determine the length to cut spokes, add the desired dimension of the base, plus twice the height of the sides, plus 8 inches for each spoke to be turned down.

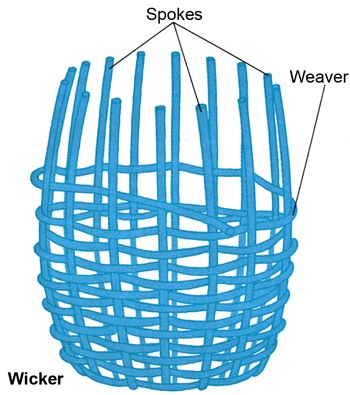

Wickerwork and Twining

Experts usually classify wicker and twining as two distinct types of basket making. But the practicing basket maker finds much overlap between the two; it is impossible to learn one without becoming acquainted with some materials and techniques of the other.

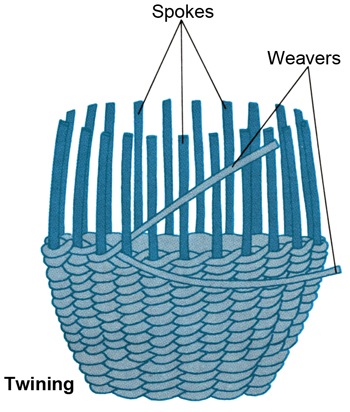

Spokes and weavers.

Both wicker and twining are composed of spokes that create a framework and weavers that hold the spokes in shape. Strictly speaking, a wicker basket is woven with one weaver in motion, whereas twining always involves two or more weavers that are twisted between spokes. In practice, twining is often used in wicker baskets, particularly for strength at stress points.

A wicker basket has a hard, twiggy look. Its spokes and weavers are usually stiff rods of willow, reed, or cane. Wicker baskets bring to mind traditional European and American forms—the market basket, the picnic hamper, the fishing creel, the Irish potato basket, for example—but wicker baskets are found in a multitude of forms from the Orient to South America.

Twined baskets occasionally have reed or willow spokes, but more often the spokes are a softer material, and the weavers are always more flexible than those in wickerwork. The basket gets its firmness from the twisting of the weavers between the spokes. A twined basket may be so finely woven that it looks like fabric.

Soaking materials.

The secret to working stiff material into a round form is in soaking it until it is pliable. The thicker the material, the longer the soaking required. If the material begins to dry while you are working, give it another soaking until its pliability returns. But never leave an unfinished basket wrapped in wet towels or plastic overnight because it may become mildewed. Let it dry and re-soak it.

Before breaking open a bundle of reed, soak it (otherwise the strands become tangled and break easily). Then make a coil of each separated strand, tie it in the middle, and leave it in the tub. When you need a new reed, you will not have to disentangle it.

Every basket maker weaves differently; some work tightly, others loosely.

The Initial Spoke.

Always mark the initial spoke—where you begin weaving the first round—with a Piece of thread or raffia. Begin any changes in weave at that spoke.

The History of Basketry

Burke Museum on the West Coast has a page on “Northwest Coast Basketry” that is very interesting.

Reference: Readers Digest Crafts & Hobbies – A Step-by-Step guide to Creative Skills.

& Wiki Commons.

One Response

Beautiful Baskets - Crafting DIY

[…] Basket Making An Ancient Craft […]